Every winter, the energy world gets its version of groundhog season.

A major national report drops. Headlines follow. Social media lights up. And suddenly we’re told again that the power grid is on the brink of collapse.

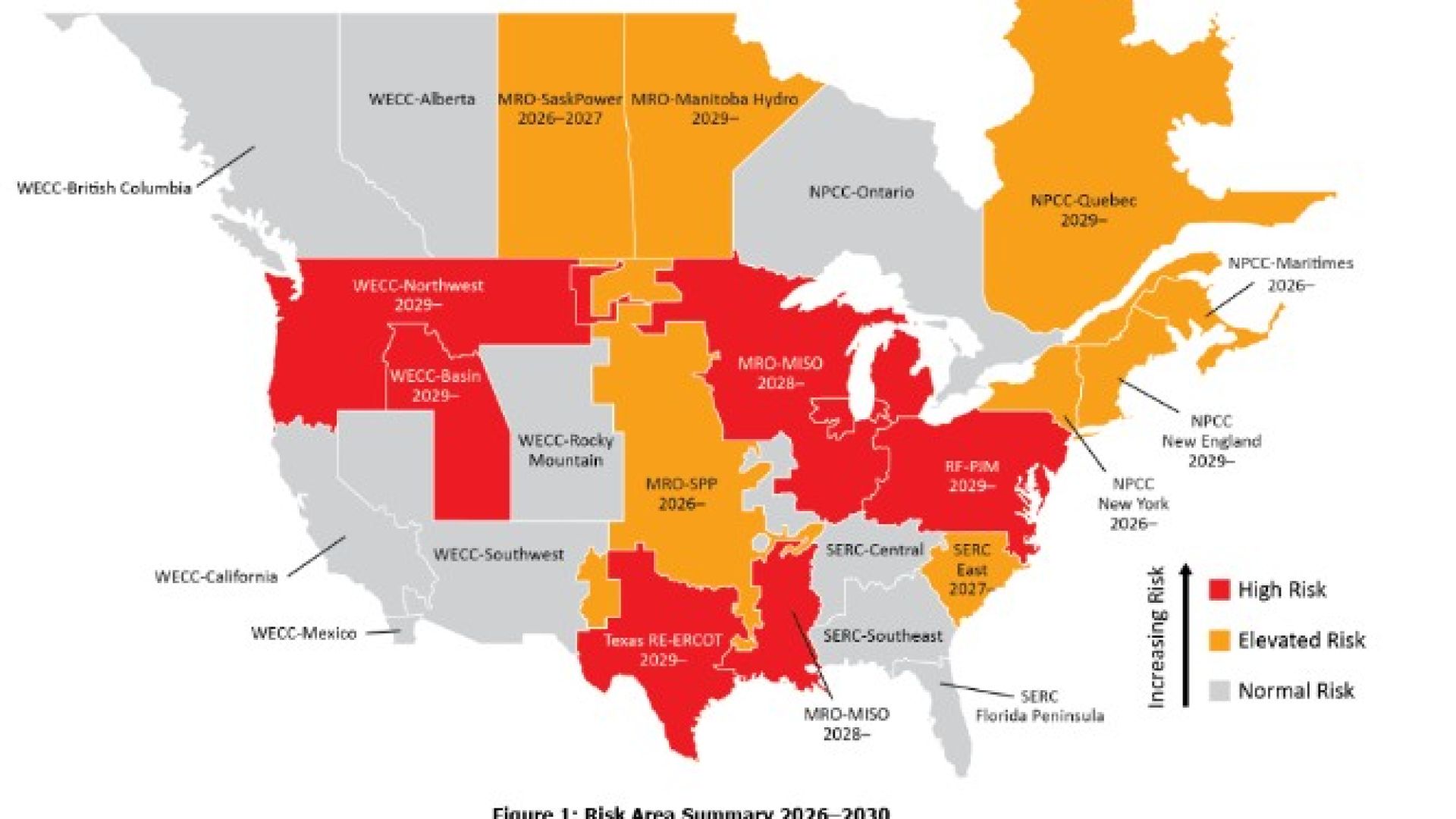

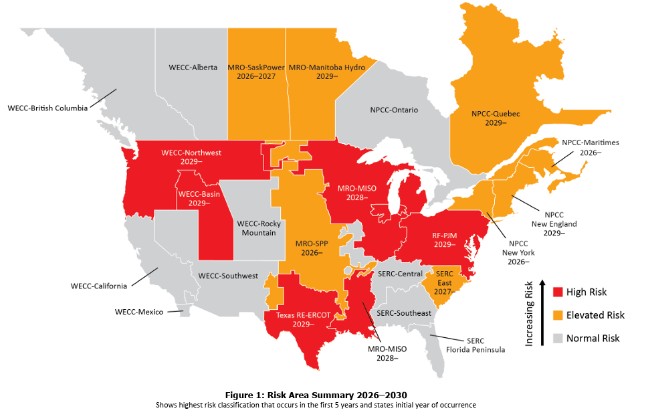

This year’s edition comes from the North American Electric Reliability Corporation’s (NERC) Long-Term Reliability Assessment (LTRA). If you’ve seen the color-coded maps, you know the vibe: large swaths of the country glowing orange and red, signaling elevated or high reliability risk.

Cue the familiar refrain: The sky is falling. We’re running out of power, and we need to build things fast.

Before anyone hits the panic button, though, it’s worth slowing down and actually reading the fine print because the story the maps tell and the story the report actually supports are not the same thing.

First: This is Not a Forecast (NERC Says So - Repeatedly)

To NERC’s credit, the report is very clear about one thing: This is not a prediction of the future.

The LTRA is a snapshot in time, built using data submitted months earlier, in this case, largely from July 2025. Any changes after that point, ie., new generation approvals, updated load forecasts, revised interconnection timelines, are often missing.

That matters a lot in 2026, because the electric sector is changing at warp speed.

Load forecasts are being revised.

Data center projects are accelerating, pausing, or disappearing.

Battery procurements are being approved between board meetings.

Expedited resource processes are pulling projects forward by years.

And yet the maps freeze all of that motion into a single still frame, and then present it as a continent-wide reliability warning.

That’s… not ideal. Nor is it reality.

A Very Long Game of Telephone

There’s another issue that deserves more attention. NERC does not independently develop the load forecasts or resource plans used in the LTRA.

Instead, the process works like this:

- Local utilities develop forecasts

- Those forecasts are submitted to RTOs or regional reliability entities

- Those entities aggregate and standardize the data

- The results are then passed up to NERC

By the time NERC receives the inputs, they are already several steps removed from their original source. NERC staff are not auditing utility assumptions. They are not independently modeling IRPs. They are not re-forecasting data center load.

They are at the end of the line.

And while that doesn’t make the report malicious, it does make it fragile. When assumptions are uncertain (and right now, many are), that uncertainty compounds as it moves upward.

The result is a polished national report built on inputs that are already outdated by the time it’s published.

When the Numbers Don’t Line Up

This helps explain some of the head-scratching results buried in the assessment:

- Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO) is labeled high-risk even though NERC’s data are missing about 20 gigawatts (GW) worth of gas and battery plans over the next 5 years. Per NERC: “ERAS projects are not in the model for the 2025 LTRA. If ERAS projects come in as currently planned, the projected reserve margin shortfall would be eliminated.” Instead of showing the planned units coming online,the report says MISO has a net loss of gas units by 2030.

- Southwest Power Pool (SPP) shows extremely high reserve margins, yet still appears on risk maps based on scenario assumptions that exclude resources currently being pursued through expedited processes. SPP has over 15 GW of generation undergoing accelerated review via ERAS, but only 781 megawatts (MW) of power are shown as being added by 2030 per NERC. The report also shows SPP with a net loss of natural gas generation, even though almost 10 GW are currently undergoing the fast-track interconnection process. NERC’s data suggests that zero megawatts of solar will be added over the next five years. Zero.

- Parts of the Southeast show 30%+ reserve margins and still register unserved energy in probabilistic models, a result that is difficult to reconcile in plain English and even harder to explain to policymakers. SERC-East, Duke Energy’s territory, evidently had some sort of winter load data error, but according to NERC, that resulted in, “We are unable to rerun the model in time for the submission.”

- Battery storage additions approved by utility boards in recent months often do not appear at all, simply because they occurred after the data cutoff (one of the many benefits of storage is that it can be deployed fast). TVA’s Board recently approved adding 1,500 MW of new battery resources by 2029, none of which show up in the NERC report.

Of course, none of this means reliability should be ignored. But it does mean this assessment should not be treated as gospel.

To Be Clear: This is Not an Attack on NERC

Let’s say this plainly - NERC’s technical staff have one of the hardest jobs in the energy sector.

They are trying to assess reliability across an entire continent while:

- Load growth is historically volatile

- Technologies are evolving rapidly

- Planning rules differ by region

- Interconnection timelines are unpredictable

- And policy signals are changing in real time

That is not easy work.

The problem isn't that NERC analysts are careless. The problem is the product: a static, color-coded “risk map” that creates a false sense of certainty in a highly uncertain moment.

Why the “Maps of Doom” Are Not Helpful

These maps are already being teed-up in legislative hearings, regulatory filings, and media articles as justification for:

- Bypassing competitive procurement

- Fast-tracking utility self-build projects

- Locking in long-lived fossil investments

- And sidelining lower-cost clean energy resources

Meanwhile the public is seeing rising electric bills with a less reliable grid. People make decisions based on NERC reports, even if NERC attempts to dissuade just that.

So, What Should Policymakers Actually Take from This Report?

If read carefully, the LTRA supports a very different set of conclusions. Planning processes must be flexible. Load forecasts must be revisited frequently. Interconnection timelines must improve. Storage, transmission, and demand-side solutions matter.

One-size-fits-all solutions do not exist.

What it does not support is panic. Reliability is critically important. So is affordability. So is competition. We can — and must — do all three at the same time. But that requires careful planning and reading the fine print and between the lines.